|

Pedro de ANDRADE

Faculty of Economics, University of Coimbra, and CITIDEP Portugal.

R. Tristão da Cunha 34, 1400-349 Lisbon, Portugal. E-mail:

pedro.andrade@individual.eunet.pt

ABSTRACT

In the contemporary global world, occurs a cohabitation processus involving four central modes of interpretation of reality: Science, Information Technologies, Art and Religion. Each one relates to a specif form of power and may constitute the arena of new forms of dialog or conflict between two paradigmatic forms of society: democracies and fundamentalisms. The main strategies used in this global contact or contract develop through struggles for hegemony. The corresponding tactics are: (a) the social clonation, or reproduction of societies in terms of dependent social systems, which imitate, the most perfectly they can, the original one; (b) the social translation, meaning the social and symbolic modes of passage or transformation from a type of institutions to another, inside the same society or among different social formations; (c) the over-dichotomization, which denotes the proliferation of social dichotomies or other conflictual social relations, as a 'tree' net form, among other possible configurations.

In contemporary democracies, we observe the cohabitation of two

hegemonic modes of interpretation of reality, closely associated

with modernity: science and technique. These hermeneutics emigrated,

gradually, towards the totality of the social fabric, in particular

through the generalized diffusion of new technologies. Moreover,

late modernity - - or, according to some authors, post-modernity

-, has been reintroducing two other discourses which (as the precedent

ones) maintain some ambiguities. First of all, art. Jean-François

Lyotard argues that art can propose a credible alternative to

the 'grandes narratives' underlying modern rationality.

The second renewed discourse, religion, shows a notable progress,

insuspected until recently, concerning its influence upon our

contemporaneity. The dichotomy 'sacred /profane' became more visible

in the last decades, for common citizens, above all through the

enunciations of fundamentalisms.

The relationship of these four discourses with the political sphere,

mainly in terms of exercise of democratic citizenship and public

opinion, doesn't become transparent as well. In a global dimension,

one of the most problematic interfaces, related to this subject,

refers to recent reformulation of the role of religion in political

life, operated, partly, by integrisms. The more radical versions

of these political extremisms inspired by religion, consider a

scenario of confrontation between two paradigmatic forms of society:

democracies and fundamentalist theocratic societies. Such change

within international relations derive, among other factores, from

the emergence of a new global protagonism, the opposition North

/ South, in detriment of the previous main international tension

between East and West, that characterized the Cold War period.

Nevertheless, the analysis of the new world order cannot reduce

to this 'North/South' vision of conflictuality, somehow simplistic.

In particular, it becomes risky to just foresee an unique 'liberalization',

'democratization', or 'transition for democracy' constructed by

non-western societies in direction to a 'global democratization',

or towards other paradigmatic flags of western societies. Inversely,

at least three other main scenarios can happen: (a) a counter-transition,

that is, a process that refuses the route for democracy, inside

those 'pre-democratic' societies; (b) a lesser / deeper fundamentalization

of the West; (c) or even a global fundamentalization. We may note

that fundamentalisms have already been detected in the very interior

of democratic societies, in several social spheres. We called

such process social fundamentalisms. 1 In the worst scenario,

the development of fundamentalisms can produce, in the next decades,

a sort of 'political volcano', that is, a process characterized

by a sucession of 'social lava effects'. These social lava effects

mean the incontrolated spread of fundamentalization phenomena

of different types, in multiple localities of the world system

and, in particular, within several social spheres, not just in

political or ideological spheres. In the contemporary arena, the

relative invisibility of these effects result, in part, from the

omission of reflexivity by some sociologists or other political

analysts.

How can we situate these discourses, ideologies and socio-historical

processes within the economic sphere, that determines them, in

a great extent? We know that comtemporary democratic societies,

in a bigger or smaller scale, are based on capitalist systems

historically located in the period of disorganized capitalism,

in the words of Scott Lash and John Urry, or post-fordism,

accordig to David Harvey. As for fundamentalist societies,

they correspond to production systems: (a) in transition towards

industrial societies; or (b) in direct passage from pre-industrial

societies to postindustrial societies; (c) existing also the possibility

of a counter-industrialization, that is, a retreat of economies

predominantly commercial or relatively industrialized towards

less industrialized economies, but based, for example, in financial

dynamics, like the speculation on the price of oil. Counter-industrialization

occurs, often, in alliance with re-tradicionalization, this last

concept meaning a certain reactualization of economic, political

and cultural traditional values, as Arab tribalism and nomadism.

Under the perspective of world economy, studied by Immanuel Wallerstein,

2 democracies can be included, tipically, within central societies

or in semi-peripherical ones, and fundamentalisms coincide, usually,

with peripherical societies.

In this globalized world, both paradigms of social formation suffer,

in the contemporary arena, multiple effects from information technologies,

which are some of the most crucial elements within the new economic

and societal regulation operated by disorganized capitalism and

post-fordism.

The 'net society' (using a Manuel Castells's concept) produced

by this historical context, organize social spheres in a reticular

way, that is, their multidirectional interaction is meaningful

in original ways. One of these alliances between social spheres

is the growing protagonization of Science in everyday life, vehiculated

by information technologies, which, in some way, reify sience.

In the last decades, an opposition to this sience-IT dyad ocurred,

personified by Art and Religion. An illustration of this new articulation

of societal spheres is genetic information. Such a scientific-technical

knowledge, included in the discursive sphere, after having been

promoted by influent economic interests, conditionate the organization

of work and employment, for example in recruitment terms. So being,

genetics abstains from behaving as a 'gene ethics'.

"Recent studies suggest that employers are becoming interested

in using genetic information about employees when the capability

arises. () Perhaps the most pressing of all the daunting moral

questions presented by genetic screen is whether society should

make all of the potential technologies available ". (Boyle,

1996: 206) 3

In the meantime, recent transformations modify even the nature

and notion of space and time. From Einstein's theory of relativity

- opposed both to 'angelic' essencialism and to pure relativism

- physical and social spaces cannot be understood without their

respective temporalities. This irreversible change was clarified

in information societies by the concept of 'compression of space

and time' (David Harvey, Anthony Giddens). And besides cyberspace,

it is necessary to reflect on the dimension we designated cibertime,

that is to say, the different temporalities underlying human activities

undertaken in information networks. 4

In this complex context, how to detect, then, the double porosity

between democracies and fundamentalisms, maybe the two most important

society paradigms in our contemporaneity?

(a ) In other words, on one side, in what way is drawn the contact

between these two social formation models and considering their

whole, in situations of dialog and/or discordance?

(b) on the other hand, how is processed the permeability among

social spheres, both inside democratic societies and inside fundamentalist

societies, and how these new connections among spheres translate

the widest articulation among social formations where these spheres

work?

As mentioned above, after the collapse of State communism and

the end of Cold War, in terms of international relations, the

world system passed from a bipolar structure (dominated by the

opposition between West and East) to a multipolar structure, where

multiple dichotomies of interests coexists, less or more pacifically

(South versus North, the 'clash of civilizations' that Huntington

circumscribed,and so on.).

"In the post cold war world the most important differences

among peoples are not ideological, political or economic. They

are cultural. Peoples and nations are trying to answer to the

most basic question human beings face: who are we? And they answer

to this question in the most traditional way, having as reference

what is more important for them. People define themselves in terms

of origin, religion, language, history, values, habits and institutions.

They identify themselves with cultural groups: tribes, ethnic

groups, religious communities, nations and, at a wider level,

civilizations. People use politics not only for promoting their

interests, but also for define their identity. We only know who

we are when we know who we are not and, frequently, against who

we are ". (Huntington, 1999: 28) 5

However, contrary to Samuel Huntington's thesis, other authors,

like Shireen Hunter, underline that this incompatibility doesn't

possess essentially a cultural nature, but need a more political

interpretation. Some of the facts that support such an hypothesis

are the following ones: a few decades ago, the Sha of Iran, (occidentalized

country but still presenting strong influences from other civilizations),

maintained good relationships with the West and the same happens

today in certain Muslim societies where islamism constitutes the

center of social and political life, as Saudi Arabia.

"... the underlying but largely unspoken and unacknowledged

cause of the dichotomy between Islam and the West is the question

of power and the consequences of its exercise - that is, influence

at the regional and global levels. This balance of power, which

is heavily weighted in West's favor, gives the West a tremendous

influence on the fate of the Muslim states and peoples (...) through

a variety of financial and military means (...) including support

for regimes and governments that are less than reasonably supported

by the majority of their own people ". (Hunter, 1998: 19-20)

6

In this conjuncture, a single superpower, the USA, emerges as

the hegemonic and basic regulating force regarding the myriad

of world conflicts which acquired a new protagonism in the last

decade. A reaction to such a situation is the recent mutual atraction

among Russia, China and India. Although not formalized in terms

of a global political or economic counter-hegemonic block, this

potencial alliance intends to compensate, in a still hesitating

way, the American hegemony demonstrated in the Gulf, in Bosnia

or in Kosovo.

However, 'hegemony' is a concept that appears to be problematic,

for two reasons. Firstly, due to the non uniform use of this concept

by different authors, namely Marxists. Secondly, because hegemony,

in contemporaneity, is changing deeply in its nature, in my opinion.

Regarding the first aspect, the term 'hegemony' receives four

basic significances in Marxist texts: first of all, it gets the

connotation of 'dominance', in the usage made by Mao Tse Tung

for the term 'hegemonism', apllyed by him to signify the dominance

of a national State on other, domination different from imperialism.

Besides that interpretation, hegemony

means 'leadership', articulated to the idea of a certain 'consent',

that coincides with the most usual sense in Marxist tradition.

Lenin himself, but also its enemies, the menchevics, applied this

concept as a synonym of political leadership in a democratic revolution,

in terms of an alliance with peasants' fractions. Although Bukharin

and Estaline equally used this term, it is with Gramsci that it

acquires a decisive sociological depth.

The third meaning of hegemony, rarely visible in the writings

of Gramsci previous to Quaderni di Carcere, refers

to 'alliance strategies' of the working class with the 'peasant

class' or others. A similar meaning was present in the debates

inside the Communist International.

Finally, the fourth idea of hegemony, and undoubtedly the more

fruitful, is the one revealed in Quaderni di Carcere

(1948-51).7 Here, hegemony is defined as the way through which

bourgeoisie constructs and reproduces its dominance. For Gramsci,

the bourgeois State obtains hegemony by force articulated to consent.

The 'historical block' is a system of alliances among social forces

led by bourgeoisie, by means of some concessions, to other socio-political

partners. The hegemony built in this way by the dominant class

(in such a context also called the 'hegemonic class'), leads to

a certain consensus and social balance. The 'texture of hegemony'

is processed and promoted inside specific institutions by 'organic

intellectuals'. The institutions of hegemony are located in civil

society, and the State is the arena of political society, although

both instances form an articulate and sometimes coincident social

unit, in Gramsci 's point of view. Such an interrelation appears

reinforced in Ben Eliezer's essay on the hegemonic nature of Israeli

civil society (1998). 8

As for the second problematic dimension of hegemony, when refering

to the contemporary international arena, we observe the following

points: states, superstate organizations or other global partners,

don't just intend to reply to a given hegemony and, tendencially

or eventually, substitute it for another. This is a simplistic

and somehow naif vision of international relations. On the contrary,

we observe today not only the appearance

of multiple hegemonies of different nature

in relation to previous ones, but we assist

to hegemony struggles based partially in

unseen terms, at world level. To justify

and develop this main proposition, we will purpose the following

ten arguments.

Thesis 1 : disorganized post-fordist capitalism creates

the conditions for the emerging of original

forms of domination, leadership and alliance.

In particular, post-fordist capitalism contributes

for the appearance of plural hegemonic forms,

which will be nominated flexible hegemonies.

In the first phase of capitalism, the local forms of hegemonies

follow a single and main paradigm of regulatory legitimacy,

analized by Gramsci, like French Revolution or Risorgimento.

These are examples of rigid hegemonies. We know that non-hegemonic

forms of domination, like democracy, don´t present themselves

as the sole model of political action, or as the the single paradigm

of society, but only as a more efficient political system, among

the possible ones.

More recently, flexible hegemonies can be defined as hegemonies

not completely regulatory, but constantly evolving inside a process

of auto-legitimation and re-legitimation, according to a particular

global conjuncture and adapting to each locality inside the world-system.

The more dynamic forms of flexible hegemony (as well as the non-hegemonic

forms of dominance) exhibit different degrees of partition of

power, force or consent. However, flexible hegemonies don't possess

an opening to alterities of interests, as versatile as non-hegemonic

forms of domination, although flexible hegemonies appear as being

more receptive than rigid hegemony forms. Today, 'neo-liberal'

hegemony is understood by Bieling and Deppe (1996) 9 in terms

of global capitalism. According to this author, neo-liberalism

manages to produce a consent based on a new historical block,

the European Union beeing an example of this process. He argues

that hegemonic planetary structures are filtered by European national

institutions, which legitimate them indirectly. In particular,

American managerial hegemony has already been analized by Gramsci,

who pointed to one of the most notorious characteristics of Fordist

capitalism, which is the new relationship between man and machine

transmitted by taylorism, which reduced the worker to the status

of a 'trained gorilla'. Yanarella and Reid (1996) 10 say that

this relationship, in post-fordism, can be sumarized by the concept

'humanware', to translate the work atmosphere that articulates

'hardware' and 'software'.

That beeing said, here is our

second argument regarding this problem of global hegemonies:

In the actual conjuncture of international relations,

strategies of global protagonization are beeing

developed by certain society paradigms, each

one of them seeking to acquire, a priori,

a situation of single centralism, in

detriment of the remaining society models.

Or, if this situation is not possible,

due to the relative balance of power in

the world forces correlation, the global

actors who intervene in the struggle of

hegemonies intend to arrive to a situation

of negotiation of centrality. We are facing, in

the first case, an exclusive hegemony and, in the second case,

a shared hegemony. Both can be understood as particular forms

of flexible hegemony. The back stage of this struggle and negotiation

of hegemonies is transnational capitalism. Leslie Sklair (1997)

10 applies the concept of hegemony to detect hegemonic practises

led by the transnational capitalist class, which is supported

by multinational companies and by a culture of global consumerism.

The agents of this global consumerism are managers, bureaucrats

and transnational politicians, as well as consumist elites. We

can also remark that:

Thesis 3: flexible hegemonies are not reduced

to the spheres of political and cultural

domination, but they are unfolded, in

post-fordist capitalism, in a plurality of

specialized hegemonies, that is to say,

hegemonies corresponding to each sphere of

social interests. Gramsci underlined cultural components

of domination that, articulated to given political condicions,

define hegemony as produced by a class on another. What disorganized

post-fordist capitalism adds to this picture is a dissociation

among social spheres, in a somehow artificial way, intending to

grant a certain independence to each one of them. For example,

specific forms of cultural hegemony are testified by different

getekeepers of culture, regulating several niches of cultural

industries, as art critics, curators, auctioneers, research journalists,

documentalists, librarians and archivists. Another example of

this process of social spheres fragmentation is 'moral regulation'.

Gramsci identified it as one of the elements contributing to Fordism

hegemony, through the analysis of the agents providing moral regulation

in terms of sexuality control and alcohol consumption by workers.

Alan Hunt (1997) 11 shows the importance of that mode of hegemonic

regulation in the government decisions and projects in contemporary

society. On the other hand, hegemony is also exercised, particularly,

in political and cultural consents around gender, like the domination

due to the myth of masculine superiority. Under this perspective,

Kornelia Hauser (1996) 12 characterizes the ideology of heterossexuality

as hegemonic and sexist.

In a general way, those flexible hegemonic strategies - exclusive

or shared, general or specialized - can be subscribed by any of

the more influential political systems, but they acquire a more

radical posture namely in the relationships between democracy

and fundamentalisms, especially, for the last ones, in the case

of fundamentalisms of Islamic obedience.

Inversely, the possibility of counter-hegemony exists inside these

societies, in their several levels (Schaffer, 1995), 14 or mobilized

by citizens in the context of American urban movements (McGovern,

1997). 15 At planetary level, global social resistance is equally

possible, meaning the mobilization of dominated transnational

classes towards emancipation, or the alternatives to state political

structuration advocated by non-state transnational organizations

or associations of people interests, environmentalist mouvements,

Internet citizens, and so on. (Andrade, 1996) 16

Another concept that can attest reciprocal influence between democracies

and fundamentalisms is 'sincretism', defined as the fusion of

cultural traditions inherent to different societies and, in particular,

social norms and religious habits. However, a critical posture

is necessary to this concept, because the social processes from

where sincretism derives appear, often, as problematic and ambiguous.

"In many such contexts, the penetration of Western forms

of capitalism and cultural hegemony has been - paradoxically

both subverted and promoted through sincretism. (Stewart, 1994:

21) 17

On the contrary, multiculturalism, interculturalism and transculturalism

are more stimulant, especially when the periferic societies (where

some of their agents come from) contribute to the reconstruction

of identities inside central countries. Such a process is reinforced

by the new emancipatory conscience underlying post-colonial movements

and theory. In fact, in the cases of dialogic or conflituous contacts

between democracies and fundamentalisms, we are coping (partly,

although not completely) with 'multiculturalist' processes, like

Charles Taylor underlines, or with interculturalist processes,

in Scott Lash sense (1994). 18

"At the present time, several different political groups

focus on the necessity - sometimes exigency of legitimacy.

The necessity (it is possible to say it) constitutes one of the

forces underlying nationalist movements. As for the exigency,

it stands out in different ways, inside the present politics of

minority or subordinate groups, in certain forms of feminism and

in what is called today the politics of 'multiculturalism' ".

(Taylor, 1994: 41) 19

es not only in the cultural sphere, but as well inside all the

societal spheres of interests. In other words, such fusion becomes

visible not only in a abstract and uniform way, but acquires specific

contours in each society or in each social sphere where it acts.

For example, Bahaba (1990) 20 and Haraway (1990) 21 have demonstrated

that the hybrid identities are characteristic of the post-colonial

societies. Though, from those periferic localities of the world-system,

multiple hibridization flows circulate to the central countries,

or, on the contrary, they have origin in these countries. Furthermore,

hibridity allows the critic of power relationships in new ways.

Crompton (1993) 22 defends that in the confluence of the socio-economic

sphere with the discursive sphere, pure class identities don't

exist. The deep transformations of capitalism, mass unemployment

and generalization of education contributed to different forms

of class hibridity. On the other hand:

Argument 4: not only hibridity articulates different

societal natures within themselves, but each

fusion form joins other forms of social creolization,

according to societies and spheres of interests

where it interferes. In other words, hibridism understood

as a unidimensional form or as a multiculturalism concentrated

in the cultural sphere, should be overcomed by the process that

we nominate meta-hibridism. Meta-hibridism means, then, the hybridization

of several hibridities. Some examples of this phenomenon (ocurring,

more visibly, in one or in another society / social sphere) are:

the fusion among identity hibridities; the synthesis of economic

systems previously articulated; the contamination among fusions

of differential types of power. However, we would like to underline

this: the backstage of such processes of complex and multi-phase

hybridization have its roots - both in their conservative forms

and in their progressive ones - in the economic sphere. That is,

at present time, they occur within the structures and characteristic

processes of disorganized capitalism and post-fordism, as mentioned

above.

Post-fordism engenders, in particular, risk phenomena. Deregulation

in national level (and re-regulation in global level, which frequently

follow deregulation), driven to all societal spheres, constitute

a necessary condition for post-fordist flexible accumulation at

this planetary level, producing a contingency social atmosphere.

The effects of this process may give rise to uncontrollable environmental

disasters or, in the scope of our study, they may be revealed

in the conflict among two society paradigms a priori incompatible:

democracies and fundamentalist regimes. Against these global menaces,

that can both drive to the annihilation of populacional masses

in minor or larger scale, or even to the destruction of the entire

planet, Ulrick Beck (1992) 23 defends the need to develop a process

of reflexive modernization, that is to say, the mobilization

of colective reflexivity to surmount the inadequacies derived

both from modernity and post-modernity.

In my point of view, for the accomplishment of the mentioned strategies

inside this global scene, three main tactics have been mobilized

by the most prominent historical models of social formation, and,

at the present time, mainly by democracies and fundamentalisms.

The first two are structural tactics, that is to say, they can

provoke important structural changes, corresponding often to precise

historical moments in the life of the involved societies. One

of those structural tactics is social clonation, which has two

main forms: inter-societies cloning and intra-societal cloning.

Statement 5: Inter-societies cloning can be understood

as the reproduction of a society paradigm

inside other societies, more or less different

from the first. By means of this movement, the first

one acquire the status of cloned societiy, and the second ones

are inscribed in the situation of cloning societies. In other

words, these last societies become, frequently, social systems

dependent from the first ones. This process is more visible in

the economic and cultural spheres, but it overflows to other less

detecteble spheres, like the political sphere.

In this first type of cloning, the exportation of a society model

to other locality of the world, in substitution of a previous

and different paradigm, presents the following three main variants,

for more recent periods: (a) the difusion of the American democracy

model, since the 18th century; (b) the exportation of communist

societies, in the 20th century; (c) and, in the present conjuncture,

the spread of Islamic fundamentalism based on Shi'ah ortodoxy.

This last phenomenon does not always coincide with the propagation

of islamism in general. In fact, islamism was widespread since

the 8th century, and when that happened, was usually based on

the Sunni variant, being the Shi'ah Islamic fundamentalism one

minority version of islamism, among other characteristics. Applying

some concepts used by Farshad Aragui (1998), 24 the 'discourse

of development', which can be connected to the 'hegemony of modernism',

is changing today into the 'discourse of globalization', and corresponds

to the afore-mentioned models (a) and (b) of transnational clonation.

However the (c) type of social formation can be included in a

original clonation strategy, this meaning the internationalization

of a periferic social paradigm (fundamentalism), and no longer

just a exportation of a central model.

Argument 6: intra-societal

cloning consists in the reproduction of a

social sphere based on the model of another

sphere, inside a given society (please note

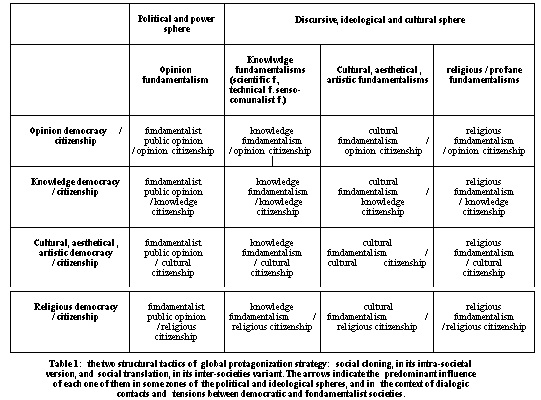

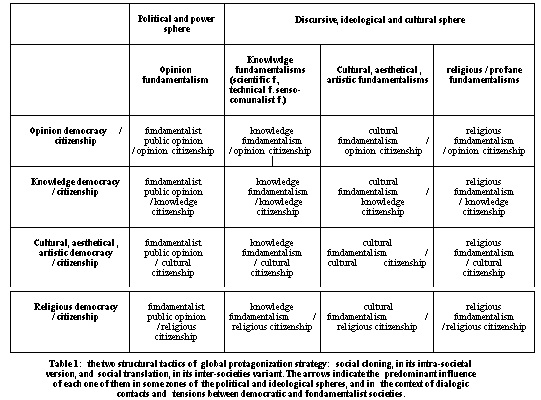

the direction of the arrows in Table 1). In the case of the Islamic

fundamentalism with Shi'ah orientation, what is exported (internally)

are the characteristics of the religious sphere. In other words,

the attributes of Allah are partially imitated by the maximum

representative of this supreme entity in Earth, the Iman, as the

infallibility. One of the results of this clonation inside Islamic

fundamentalist society can be situated at the political sphere.

This is the case of the political leader with unquestionable authority,

that in fact coincides, first of all, with the own Iman, but,

besides, can be reproduced, at a smaller scale, in an inferior

level, that is, by other elements of the religious-political pyramid.

Another sphere that suffers influence from religion is the socio-economic

sphere itself. In fact, the regulation of society and economy

obeys to a rigid and traditionalistic model. However, this regulation

derives from certain infra-structural characteristics, this time

more associated with modern western societies, for example the

industrial oil exploration.

This second type of social clonation depends on the contemporary

society we take in consideration. In democratic societies, intra-societal

cloning occurs in several directions from a sphere to another,

in opposition to what happens in Islamic fundamentalism paradigm,

as we just saw. For example, in our post-colonial planet, the

'sub-altern' concept, proposed by Gramsci, is applied by Colin

Graham (1996) 25 to verify the sub-alternization that gender suffers

in relation to the proclaimed protagonism of nationalism, in the

Irish society and culture. In other words, the political sphere

overlaps, in this situation, the sphere of sexuality.

The second structural tactic is social translation, that is to

say, the social and symbolic modes of passage, substitution, interpretation,

negotiation, version or transformation, from a type of institutions

to another, inside the same society or in different social formations.

26 This tactic does not coincide with social clonation: in the

case of this last one, an institutional or social model overlaps

other; differently, in social translation both models negotiate

with each other. In this situation it is also possible to think

about the intra-societal translation, that is, a negotiation that

takes place inside a given social formation. In such a case, notice

that religious conflicts can't be reduced to that, as they often

dialogue or collide with other types of social conflituality.

"Few concerns of social life can lead as readily to conflicts

as the combination of religious differences with other forms of

struggle. In the tweentieth century, the twin crises of modernism

and multiculturalism have added a religious dimension to many

ethnic, economic and political battles, providing cosmic justifications

for the most violent struggles. Multiculturalism produces complex

patterns of conflict both between and within religious traditions

that feed off one another and often intensify over time. Given

the destructive capabilities of modern weaponery and the consequent

necessity for peaceful coexistence, the potential for religious

traditions to promote either chaos or community becomes a crucial

factor in the global village." (Kurtz, 1995: 211) 27

Thesis 7: the direction of intra-societal translation

- represented in Table 1 by the orientation

of each arrow - in each one of the

questionned societies, drifts from the influences

associated to relative, historical and social

development of these spheres. Thus, the economic

sphere, although being decisive in all societies, acquires a notable

protagonism in democratic societies. That is to say, organized

capitalism, in its concurrencial or monopolist period, and disorganized

capitalism, informs the political sphere in a great extent, structuring

sometimes the parlamentary democratic system, other

times the democracy of parties, or the opinion democracy,

to retake the tripartite typology of representative democracy

phases, proposed by Bernard Manin and reused by Alain Minc. Diacronically,

representative democracy succeeded to direct democracy,

and preceded participative democracy.

Therefore, democratic legitimacy does not present itself unalterable,

but acquires several historical forms. In other words, each one

of its participative and citizenship activities, e.g. the vote,

should not be considered in a abstract way. This means that these

practices aren't necessarily valid for all members of the civil

society and for the generality of the world-system, specially

if they derive from a single model and if they don't suffer any

local adaptations.

"The limits of a theory of politics that derives its terms

of reference exclusively from the nation-state become apparent

from a consideration of the scope and efficacy of the principle

of majority rule; that is, the principle that decisions that accrue

the largest number of votes should prevail (...) Problems arise,

however (...) because many of the decisions of 'a majority' or,

more accurately, its representatives, affect (or potentially affect)

not only their communities but citizens in other communities as

well." (Held, 1998: 337) 28

In our perspective, inside the articulation of the economic sphere

with the political sphere, this form of assessement of democratic

representatity, the vote, can be related, typically but not exclusively,

to the following historical-economic regimes: the logic of market

reveals itself, in a certain way, in relative majorities,

and monopolist dynamics hides, somehow, in the political form

of absolute majorities. Disorganized capitalism would correspond

to the political fragmentation raised by the interests of the

minorities of differences, that is, when each and all different

social groups achieve a non-expressive number of votes. In an

utopian society, perhaps the form of opinion represented by the

majorities of differences can appear, articulating each citizen

interests and connecting all identitary differences among people.

The legitimacy of this last political democratic citizenship system

is based in the fact that the differences of interests, in their

whole, constitute a political majority, which associates, in this

way, a qualitative citizenship to a quantitative established citizenship.

Thus, the majority of differences is neither similar to each isolated

difference (like identitary and cultural differences), nor is

coincident with absolute or relative majorities. In fact, these

last ones are supported by predominant quantitative presuppositions

and on a legitimacy forged, mainly, by the accumulation of votes.

But the whole is not always equal to the sum of the parts.

Generally, in democracy, each citizen practices an opinion citizenship,

that is to say, any sovereign citizen has the right to exteriorize

a judgement about a pertinent problem in public discussion, instead

of being only informed by the infallibility and the unicity of

belief. Gradually, democracy and opinion citizenship are prolonged

by what can be called the democracies / citizenships of knowledge

and culture. These concepts mean that, in a democratic system,

even in the axes of knowledge, culture or religion, it is possible

(and desirable) the exercise of freedom, that is, the expression

of action and thought options without coercion, together with

other social agents. Actually, Eisenstadt (2000: 70) 29 propose

that the construction of democratic societies, among other contributions,

should be fed by the incorporation of protest movements in several

social interest spheres.

"This incorporation of the exigencies, themes and symbols

promulgated by protest movements, this reconstruction of the volonté

générale, can develop in several directions,

which frequently overlap each other: first, in direction to the

redefinition of symbols or centers of colective identity; second,

through the redifinition of, at least, some premises and patterns

of regimes legitimation; third, through the defense and execution

of politics that seek the redistribuition of resources and public

rights; fourth, through the construction of social spaces where

different groups can develop different patterns regarding social,

cultural and economic activities, and to promulgate their colective

identities".

In a posture partially coincident with the previous, David Held

advocates the coming of 'democracy cosmopolitan model', in the

context of globalization, world-economy and the present interstate

political system.

"The global order consists of multiple and overlapping networks

of power involving the body, welfare, culture, civic associations,

the economy, coercive relations and organized violence, and regulatory

and legal relations. The case for cosmopolitan democracy arises

from these diverse networks - the different power systems which

constitute the interconnections of different peoples and nations".

(1995: 271) 30

In state and bureaucratic modulations of communist societies,

the political and administrative sphere is the one that intends

to prevail and to influence the remaining ones, contradicting,

in practice, the primacy of the economic base, defended by Marx.

In the case of fundamentalisms, which constitute the more recent

versions of theocratic societies, it is the discursive, ideological

and cultural sphere that is imposed, essentially through religion.

So being, in those societies, the sub-type of religious fundamentalism

becomes dominant. Actually, this religious fundamentalism exhibits

variants, according to the religion (Christianism, Judaism or

Islamism): these movements that their close evolution can be read.

In fact, reislamization, rejudaization and recristianization don't

have the same impact, the same strength, in their respective societies

putting apart the parallelism of their evolution from the

middle of the seventies. The successes and failures concerning

the 'by the top' or 'by the base' movements in relation to one

another, the modes of privileged action, the acceptance or not

of a autonomous democratic space, allow to compare their respective

intensity and to imagine their future ". (Kepel, 1992: 275)

31

However, in order to reproduce themselves, religious fundamentalisms,

situated in the cultural sphere, will necessarily have to be supported

by other internal forms of fundamentalisms, e.g. by wider processes

that contextualize them, knowledge and culture fundamentalisms.

The most evident example of this alliance between spheres and

zones of social interests, is perhaps integrism, a typical political

version of religious intolerance. On the other hand, an example

of symbolic fundamentalism is the Islamic veil. Passing from this

intra-society levels towards inter-social levels, it is also possible

to speak about 'religious democracy' in democratic societies,

as well as, in certain conditions, forms of fundamentalist opinion

can be found inside Islamic societies. This form of opinion, however,

appear somehow insufficient considering the possibility of free

option (both in instruments and in goals) that any opinion presupposes.

For example, the 'democratic' voting in Algeria that gave the

electoral victory to FIS, expresses this possibility of use of

democractic and pluralistic instruments in a first moment, but,

in a second step, serving the last purpose of integrisms, that

is to say, the unicity of religious faith and beliefs. In fact,

about this subject, Eisenstadt is clear, where noticing that fundamentalisms,

although in their aims acquire an anti-modern orientation, uses

some methods of modernity (not only public opinion, but also information

technologies, for instance mass media) to diffuse propaganda of

their ideals. Furthermore:

"Besides these aspects, undoubtly important, concerning the

relationship of fundamentalist movements with modernity, stands

the fact that these movements are characterized by a highly elaborated

political and ideological construction that is an integral part

of modern political agenda- although their orientations and basic

symbols are anti-modern. " (Einsenstadt, 1997: 1) 32

Consequently, if certain societies

accomplish better, internally, certain social spheres interests,

in detriment of others, we can expect - in the encounters and

/ or conflicts among paradigms of different societies - results

which are neither uniform nor generalized. In fact, one cannot

deduce that, in the case of economic and discursive influence

from a society on other, or even in the extreme case of military

occupation of a country by other, the influent or the occupant

society and culture reaches a widespread hegemony in a unidimensional

way. In other words, the 'intensity', the 'quality' or the 'kind'

of domination or consent can vary, depending on the social zones

inside the occupied society, for example, it can be differently

successeful in economic, discursive or military arenas. What seems

possible to reach is an articulation, less or more problematic,

among modulations of diverse flexible and specialized hegemonies.

Let us see then how the process of inter-societies translation

is developed or, in other words, let's observe the translation

that occurs among two different social systems.

Proposition 8: the porosity and hybridization among

societies in their encounters or confrontations

acquires variations, according to the involved

social spheres: that is to say, after

the dialogic contact or the clash, hybridizations

may happen according to the degree of inter-societal

translation fulfilled among involved alterities.

Let's consider the arena of relationships among, on one hand,

several forms of democratic citizenship (opinion citizenship,

or knowledge, cultural and religious modes of citizenship) and,

on the other hand, opinion fundamentalism (please revisit table

1, column 2, noting again the arrows direction). In this situation,

it is probable that democratic societies obtain advantages. Indeed,

as already mentioned, theocratic societies have a less developed

opinion capital, at least the legitimated one, and a weeker participative

base of decision by the citizen. This statement, however, must

not be, so to speak, 'fundamentalized' by the sociologist, in

a etnocentrist or eurocentric way. In fact, it is wrong to suppose

that no opinion, tolerance or secularism forms exist in Islamic

societies. Some main Muslim political tendencies, like Pragmatism,

Modernism, Tradicionalism and Fundamentalism, attest this opinion

and political pluralism, although having an intensity or a nature

somehow different from the modes of opinion manifested in democratic

societies. Relating to this matter, Azib N. Ayubi (1997: 358),

33 refers the political positioning by islamist groups allowed

in Medium East secularized governments.

"But rather than of discussing democracy (or the lack of

it) in the abstract, it would be more useful here to think in

terms of democratization as a process of transition (and possibly

of counter-transitions), and rather than talking about fullfledged

participation, representation and contestation, one should perhaps

think of terms of an inclusion / exclusion scale or continuum

... [regarding islamists in muslim governments]"

Mir Zohair Husain understands in this way the contacts among economy,

politics and religion:

"Islam is an 'organic' religion, possessing a comprehensive

code of ethics, morals, instructions and recommendations for individual

action and social interaction. [However] it is also a legalist

religion whose rules and regulations later formed the base of

a divine law governing every aspect of the devout Muslim's life

". (...) the modernization process ocurring throughout the

Muslim world has not only cause secularization, (...) which most

Islamic revivalists seek to revert, but has also led to a concentration

of wealth into fewer and fewer hands, an situation inconsistent

with the teachings of Islam ". (1995: 30-32) 34

On the other hand (see column

3 of Table 1), the more decisive knowledge capitals in contemporaneity,

that is, scientific and technical capitals, revealed themselves

more significant in the West. Although, regarding common sense,

we cannot really speak of strong unbalances, but of qualitative

differences between fundamentalisms and democracy.

A situation of relative parity in this correlation of forces appears

(see the double arrows, inside Table 1, column 4) when several

forms of democratic citizenship, visible in each sphere, find

cultural fundamentalism, which is supported by the cultures of

the communities and nations converted to islamism during the construction

process of classic and contemporary Islamic culture. Such a sintetizing

and multiculturalist Islamic culture appears, in fact, rich and

multiform, facing comfortably, for that reason, the legacies of

western cultures. To this situation has contributed a long history

of contacts and hybridizations between Arab people and varied

submitted or colonial populations and civilizations.

"As a matter of fact, tradition assimilates attitudes that

are contrary to itself, like the practices of tattoo, magic, possession

performances, traditional medicine and others. The more popular

the religion is, the more it seems that religion has trained the

aptitude to bricolage between orthodoxy and heterodoxy,

between universal and local, between local and imported ".

(Silva, 1999: 154) 35

Finally, in what concerns religion (column 5 inTable 1), the deep

investment that Islamic people dedicate to it, and in opposition

to the dominant laicization or secularization in Western countries,

allow us to assume a certain advantage, now in favor of Islamic

societies, concerning the dialogic contacts and the confrontations

happening in this sphere, between both paradigms of social system.

Though, this and other partial supremacies can be used in an ambiguous

way, in the process of articulation of social spheres, and, in

a wider level, inside the permeability between West and East.

"In macrosociological terms, the postcolonial national identity

formation is in part a response to the neocolonial economic globalization.

() The uneven accumulation of capital and the distribution of

wealth and resources on a global scale exacerbates the unequal

distribution of political power and economic resources, within

decolonised countries. At the same time, globalization is accompanied

by the spread of a political culture that historically emerged

in the West: human rights, women's rights, equality, democratization,and

so on. This intersection of cultural change and economic decline

leads to resentment and resistance on the part of disadvantaged

groups who may use 'cultural resources to mobilize and organize

opposition... even though a motivation and cause of opposition

is economic and social disadvantage (...) Political elites may

also draw on ' tradition' or 'intrinsic cultural values' to justify

their actions and maintain hegemony, sometimes overemphasizing

cultural aspects as religion, morality, cultural imperialism and

women's appearance to diverte attention from economic failures

and social inequality. " (Cheah, 1998: 310) 36

In this perspective (that reiterates the porosity and the alliances

among social spheres of interests) it is important to question

the modes of intellectuals' intervention and, in particular, the

action of possible 'organic intellectuals' (in a Gramscian sense)

inside Islamic countries.

"Integral in our discussion of the various dimensions of

the discourse is the proposition that the concept of democracy

is developed within the problem of a new Arab nahda (renaissance).

(...) In the overrriding objective to transform the Arab reality,

the general interest that guides the problematic (that is, the

search for a new project of civilization) connects with the particular

interest behind the discussion of democracy (defining the beginnings

that are to regulate the mode of relations in the political community)."

(Ismail, 1995: 93) 37

Another aspect that becomes prominent, in this relationship between

the religious arena and other social spheres, consists in the

global intrinsic nature of the principal organized monoteist religions.

For example, in Linz view, Catholicism worked as a transnational

actor, overriding the sovereignty of Nation-States, even before

the globalization of economy, politics and culture.

"There have, of course, been numerous periods throughout

history of the Roman Catholic Church's collaboration with conservative

and corporatist authoritarian regimes, most notably in Spain and

to a lesser extent in Portugal. () However, it is our contention

that, sociologically and politically, the existence of a strong

Roman Catholic Church in a totalitarian country is always

a latent source of pluralism, precisly because it is a formal

organization with a transnational base. The papacy can be a source

of spiritual and material support for groups that want to resist

monist absorption or extinction". (Linz, 1996: 260) 38

Finally, the third tactic working in the conflicts or in the dialogue

between democratic and fundamentalist societies - presented here

succintly - is a conjuntural tactic, since it involves, essentially,

diacronic processes of short duration. Inside these conjunctural

tactics are combined, in greater or smaller extent, the structural

tactics previously referred, that is, clonation and translation,

or another tactics. Concretely:

Argument 9: the process of overdicotomization can

be understood as the proliferation, usually

in the short term (in a arborescent net

shape or in another configuration) of social

dicotomies or other conflictual social relationship.

These contentious articulations that engender

overdicotomization are substantially visible in

the interactions and hybridizations between democracies

and fundamentalisms. Thus, the socio-historical contacts

among these societies risk often to be transformed in dissents

rather than consents.

Though, the dynamics that were pointed out above need a ratification,

in the empiric field of international relations in this beginning

of the third millenium. Whatever will be the historical result

of this new phase of global History, it seems pertinent to refer

this last anxiety:

Thesis 10: the strategy of centralism or, more

specifically, the strategy of single or exclusive

hegemony (usually the one that is privileged

by the society paradigms in cause, the

fundamentalisms or democracies) just reveals the

disturbing tendence of their present actuation,

after all partially common: in the first or in the

second case, that global behavior seems to subscribe,

in greater or smaller extent, a global fundamentalist

identity in gestation, being it of a religious

or secular origin, islamist or democratic.

In short, at least a thing seems to be necessary, in this context

of discordant societies, cultures or civilizations: the social

actors and the sociological authors should act and reflect more

collectively on their similarities and differences, their identities

and alterities, and submit for discussion the ways to manage new

contacts and contracts that may construct themselves in an equalitarian

way. On one hand, it is urgent to act as social actor and citizen,

inside social and cultural movements of global dimension. On the

other hand, it is necessary to reflect, as a social cientist,

in terms of 'reflexive modernization' (Ulrick Beck), or subscribing

other emancipatory theoretical perspectives. Perhaps so doing

- within the dialectics between this reflexive action and this

active reflection, applied to contemporaneity - the conflicts

underlying the eventual ´polítical volcanos' and

their 'lava effects', can be transformed, again, in dialogic contacts

. 39

NOTES AND BIBLIOGRAPHY

1 We tried to delineate a theory

of the social fundamentalisms in: ANDRADE, 1997, "Sociologia

da intolerância: ou como transformar a sociedade no terceiro

milénio", Atalaia (3), pp. 9-13.

2 WALLERSTEINALLERSTEIN, Immanuel, 1998, O capitalismo

histórico seguido de A Civilização

Capitalista, Lisboa, Estratégias Criativas.

3 BOYLEOYLE, Philip, 1996, "Genetic services, Social Context,

and Public Priorities", In Aranowitz, Stanley, et al (eds.),

Technoscience and Cyberculture, London, Routledge.

4 A first formulation of the concept

cibertime, developed in 1995, was presented in ANDRADENDRADE,

Pedro, [no prelo], 1996, "Sociologia (Interdimensional) da

Internet", In III Congresso Português de

Sociologia, 1996, Lisboa, APS. The development of this

conceptualization can be found in: . ANDRADE Pedro de, 1997, 'Navegações

no cibertempo: viagens virtuais e virtualidades da ciberviagem',

Atalaia, (3), pp. 111-124.

5 HUNTINGTON, Samuel, 1999, O choque das Civilizações

e a mudança na ordem mundial, Lisboa,

Gradiva.

6 HUNTER, Shireen, 1998, The Future of Islam and

the West: Clash of Civilizations or Peaceful

Coexistence? Westport, Praeger.

7 GRAMSCI, Antonio, 1948-51, Quaderni di Carcere,

Torino, Eunaudi. Ver ainda: Idem, 1973, Gli intellettuali

e l' organizzazione della cultura, Torino,

Eunaudi. Idem, 1975, Gramsci dans le texte, Paris,

Éditions sociales. Idem, GRAMSCI, Antonio, 1979a, Il

risorgimento, Roma, Editori Reuniti. Idem, 1979b, Note

sul Machiaveli, sulla politica e sullo Stato

moderno, Roma, Editori Reuniti.

8 ELIEZER, Ben, 1998, "State versus Civil Society? A Non

Binary Model of Domination Through the Example of Israel",

Journal of Historical Sociology, 11 (3) Sept., pp.

370-396.

9 BIELING, Hans; DEPPEEPPE, Frank, 1996, "Gramscianism in

International Political Economy: A Sketch of the Problem",

Argument, 38, 5-6 (217), Sept-Oct, pp. 29-740.

10 YANARELLA, Ernest; REID, Herbert, 1996, "From 'Trained

Gorilla' to 'Humanware: Repoliticizing the Body-Machine Complex

between Fordism and Post-Fordism", In Theodore R.; Natter,

Wolfgang (eds.), The Social and Political Body,

New York, Guildford, pp 181-219.

11 SKLAIRK, Leslie, 1997, "

Social Movements for Global Capitalism: The Transnational Capitalist

Class in Action", Review of International Political

Economy, 4, (3) autumn, pp. 514-538.

12 HUNT, Alan, 1997, "Moral Regulation and Making Up the

New Person: Putting Gramsci to Work", Theoretical Criminology,

1 (3) Aug,pp. 275-301.

13 HAUSE, Kornelia, 1996, "The

Category of Gender from a Sociological Perspective: Contribution

on the Regaining and Further Development of Socially Variable

Dimensions of Critical Theory", Argument, 38, 4(216),

July-Aug, pp. 491-504.

14 SCHAFFER, Scott, 1995, "Hegemony and the Habitus: Gramsci,

Bourdieu and James Scott on the Problem of Resistance", Research

and Society, (8), pp. 29-53.

15 McGOVERN, Stephen, 1997, "Political

Culture as a Catalyst for Political Change in American Cities",

Critical Sociology, 23 (1), pp. 81-114.

16 We presented this concept at III Congresso Português

de Sociologia, 1996, Lisbon, giving the example of the protest

made in 1996 by web surfers (who transformed their web pages in

black screens) against a law that previewed censure measures on

web contents, proposed by President Clinton.

17 STEWART, Charles; ShawHAW, Rosalind (eds.), 1994, Syncretism

/ Anti-Syncretism : the politics of Religious

synthesis, London, Routledge.

18 LASH, Scott, 1994, Reflexive

Community, International Sociological Association (ISA).

19 TAYLOR, Charles, 1994, Multiculturalisme : Différence

et Démocracie, Paris, Aubier.

20 BHABHAHABHA, H., 1990, "The Third Space", In J. Rutherford

(ed.), Identity, London, Lawrence and Wishart.

21 HARAWAY, D., 1990, "A Manifesto for Cyborgs: Science,

Technology and Socialist Feminism in the 80's", In L. Nicholson

(ed.) Feminism / PostModernism, London, Routledge.

22 CROMPTON, R., 1993, Class

and Stratification, Cambridge, Polity Press.

23 BECK, Ulrich, 1992, Risk Society: Towards a New

Modernity, London, Sage.

24 ARAGHIR, Farshad, 1998, "The Rise and Demise of the Discourse

of Development and the Internationalization of Agriculture: 1945-1998",

International Sociological Association (ISA).

25 GRAHAM, Colin, 1996, "Subalternity and Gender: Problems

of Post-Colonial Irishness", Journal of Gender

Studies, 5, (3) Nov, pp. 363-373.

26 Social translation is a concept that prolongs - in terms of the global society but also regarding its localities - the concept 'translation', with which Georg Gadamer means the modes of passage from a 'linguistic game' played by an individual or a group to another language game. Gadamer intends in this way to overcome the postulate of incommunicability among those procedures of communicative negotiation, that Wittgenstein defended. For this last author, the concept 'linguistic games' (proposed by him), should be understood as characteristic and exclusive of a 'form of life', always isolated from the other ones in communicative terms. On the other hand, Habermas will apply the concept 'translation' to the 'communicative action' that, together with 'communicative rationality', is the very instrument that enables the establishment of consent among interests a priori inarticulated, in a dialectical and emancipatory way.

27 KURTZ, Lester, 1995, Gods

in the Global Village: the World's Religions

in Sociological Perspective, Thousand Oaks, Pine

Forge Press.

28 HELD, David, 1998, Models of Democracy, Cambridge,

Polity Press.

29 EISENSTADT, S., 2000, Os Regimes Democráticos:

Fragilidade, Continuidade e Transformabilidade,

Oeiras, Celta.

30 HELD, David, 1995, Democracy and the Global Order:

From the Modern State to Cosmopolitan Governance,

Cambridge, Polity Press.

31 KEPEL,Gilles,1992, A vingança de Deus:

Cristãos, Judeus e Muçulmanos à

reconquista do Mundo, Lx, D.Quixote.

32 EISENSTADT, S., 1997, Fundamentalismo e Modernidade:

Heterodoxias, Utopismo e Jacobinismo na constituição

dos movimentos fundamentalistas, Oeiras, Celta.

33 AYUBI, Nazib, 1997, "Islam and Democracy", In Potter,

David et al (eds.) Democratization, Cambridge, Polity Press,

pp.345-266.

34 HUSAIN, Mir, 1995, Global Islamic Politics, New York, Harper Collins College Publishers.

35 SILVA, Maria Cardeira, 1999, Um Islão Prático:o quotidiano feminino em meio popular muçulmano, Oeiras, Celta.

36 CHEAH, Pheng; RobbinsOBBINS, Bruce (eds.), 1998, Cosmopolitics:Thinking and Feeling beyond the nation, Minnea polis, University of Minnesota Press.

37 ISMAIL, Salwa, 1995, "Democracy

in Contemporary Arab Intellectual Discourse", In Brynen et

al, Political Liberalization & Democratization

in the Arab World, Vol 1., London, Lynne Rienner

Publishers, pp. 93-11.

38 LINZ, Juan; StepanTEPAN, Alfred,

Problems of Democratic Transition and Consolidation,

Baltimore, The Johns Hopkins Univ. Press.

39 For a global vision of the historical process that contextualize the possible dialog or collision between demo- cracies and fundamentalisms, especially in its articulation with the economical sphere, see: ANDRADE, Pedro, 1999, "A nova sociedade e a Sociologia Histórica Interdimensional", Atalaia (4), pp. 9-26.